Lance Armstrong

The world of sport is no stranger to scandal. Many athletes - including Marion Jones, Tiger Woods and Oscar Pistorius - have tainted their images and dirtied their names through shameful acts of doping, infidelity and in the most heinous of cases, murder. But few stories of disgraced athletes have entranced the general public in the manner that Lance Armstrong's has.

Born in Plano, Texas on September 18, 1971, Lance was raised primarily by his single mother, Linda. He was an active boy and at age 10, he gravitated towards running and swimming, which eventually segued into triathlons.

Showing prowess and promise in the sport, he became a professional triathlete at 16 and was crowned the national sprint-course triathlon champion in 1989 and 1990. It was around this time, however, that he grew increasingly passionate about his favorite, and without a doubt strongest, third of the triathlon: cycling. He decided to abandon his goggles and running shoes to focus solely on riding.

It was a choice that paid off with an 11th-place finish at the 1990 World Championships Road Race, where his time became the best recorded by an American since 1976.

Lance returned to training with a burning desire to improve, and in 1992 he qualified for his first Olympic Games. He finished a disappointing 14th in Barcelona, but made a move immediately afterwards that would propel his career.

Dissatisfied with his Olympic performance, Lance turned professional and joined the Motorola cycling team. This decision made the 1993 season his most successful since he began competing. He won the "Triple Crown" - the Thrift Drug Classic, the Kmart West Virginia Classic and the CoreStates Race - and also made his debut at the Tour de France. The 21-stage race is considered cycling's apex, covering 2,000 miles, including a vertical climb estimated to be around 50,000 feet.

At the age of 21, Lance also won the 1993 World Road Race Championship in Olso, Norway. He became the youngest person to achieve this feat and only the second American.

Lance would again compete in the Olympics, placing sixth in the 1996 Atlanta Games time trial and 12th in the road race.

The year also marked Lance's first lucrative contract signing. He struck a deal with France's Team Cofidis, which included a $600,000 salary.

Devastation crashed into Lance unexpectedly when he was diagnosed with cancer in October 1996. He was given a 65 to 85 per cent chance of survival when doctors detected testicular cancer, but those odds dropped to 40 per cent when tumors were also found in his abdomen, lungs and brain.

To combat the disease, Lance underwent aggressive chemotherapy treatments and in February 1997 was declared cancer-free.

Throughout his battle with cancer, Lance remained determined to compete. He insisted he would beat his disease and return to cycling, but few shared his faith. Cofidis retracted their hefty deal and left him scrambling to find a team once he made his comeback. Lance settled for a $200,000-per-year position with the United States Postal Service Pro Cycling Team.

His spot on the new team may not have initially added as much weight to his wallet as his Cofidis contract did, but in 1999 he bolted back onto the road with an unforgettable Tour de France triumph. He became the second American to win the event, and in the process showed signs of what was to come.

Lance again claimed the Tour crown in 2000, the year he also competed in his third Olympic Games and captured a bronze medal in Sydney.

He returned to the Tour in 2001 and repeated his win.

But Lance's string of successes was beginning to spark suspicion. Irish sportswriter David Walsh was wary of Lance's smooth transition from cancer-afflicted patient to cycling's dominant performer.

In the same year Lance won his third consecutive Tour, David wrote a story that tied him to Michele Ferrari, an Italian doctor who was under investigation for supplying performance-enhancing drugs to riders. David also received a confession from Lance's masseuse Emma O'Reilly, and eventually outlined his case against Lance with a book he co-authored in 2004 called L.A. Confidential.

Despite the murmurings that were slowly starting to swirl, Lance captured an astonishing four more Tour titles from 2002 to 2005. He retired after his 2005 victory.

Not one to renounce his winning ways, though, Lance jumped back on his bike in September 2008 and raced in the 2009 Tour as part of Team Astana. At 38 years old, he placed third.

He competed again in 2010 with a new team endorsed by RadioShack, but placed an uncharacteristic 23rd.

In February 2011, he announced his permanent retirement from competitive cycling.

Lance had hoped to quietly step away from the sport, but a storm of scandal was only beginning to brew.

Around the time of his retirement, Lance's former U.S. Postal Service teammate Floyd Landis admitted to doping - he was stripped of his 2006 Tour victory for drug use - and accused Lance of the same. It was an accusation that triggered federal action.

In June 2012, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) filed formal charges against Lance. In the following months, several former teammates stepped out of the shadows and testified against him.

During this time, Lance maintained his innocence. He repeatedly stated that his cycling accomplishments were clean and honorable, and that insinuations to the contrary were "baseless."

His words held little weight, though, and in August 2012, the USADA announced that Lance would be stripped of his seven Tour wins. Any other victories he claimed between 1999 and 2005 would also be rescinded and he was formally banned from cycling.

The USADA's announcement came with over 1,000 pages of evidence. Included were laboratory test results, emails, monetary payments and scientific data, as well as a list of 26 names of people who were prepared to testify and implicate him. Of those 26 people, 15 were riders who claimed Lance used performance-enhancing drugs and acted as the ringleader behind the team's doping tactics.

Tyler Hamilton, an Olympic gold medalist who helped Lance to three Tour de France wins from 1999 to 2001, wasn't on that list. He refused to cooperate with the federal investigation of Lance out of fear that his own doping history would be brought to the surface. However, he was served with a subpoena in 2012 and ordered to testify before the grand jury. In an interview with Scott Pelley for 60 Minutes that same year, he confessed his own performance-enhancing past.

Travis Tygart, chief executive of the USADA, said, "The evidence shows beyond any doubt that the U.S. Postal Service Pro Cycling Team ran the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that the sport has ever seen."

Travis added, "The USPS Team doping conspiracy was professionally designed to groom and pressure athletes to use dangerous drugs, to evade detection, to ensure secrecy and ultimately gain an unfair competitive advantage through superior doping practices. A program organized by individuals who thought they were above the rules..."

Evidently, the culture entrenched in the sport of cycling endorsed doping. According to the USADA, 80 per cent of Tour de France medalists between 1996 and 2010 have been found guilty of taking performance-enhancing drugs.

Shortly after the USADA's release of information, the governing body of cycling - the International Cycling Union - followed suit. They stripped Lance of his Tour wins and also banned him from cycling for life.

Pat McQuaid, president of the ICU at the time, said, "Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling."

As Lance's unprecedented career was unfurling, more and more people were casting doubt not only on his achievements, but his character as well.

In a 2012 interview with The Telegraph, Betsy Andreu revealed compelling information that painted Lance in an ominous and spiteful light.

Betsy's husband Frankie was a close friend and teammate of Lance's. While Lance was grappling with news of his cancer diagnosis in 1996, Betsy was present in a hospital room where he informed doctors that he had taken performance-enhancing drugs, including testosterone, growth hormone, cortisone and erythropoietin (EPO). Betsy was one of only a handful of people to hear the confession, and it remained secret for years.

Betsy and Frankie discussed the news privately when Frankie admitted to her that he took performance-enhancing drugs, too. At Betsy's insistence, Frankie went public with his own story before Betsy targeted Lance and disclosed the confession she had kept hidden.

As a result, Betsy was subjected to sustained abuse and became the victim of brazen bullying by Lance. She was firm in her stance, though, and refused to be hushed.

On revealing the facts she knew to be true, she said, "We had to make a decision as a family whether to be on the Lance Armstrong financial gravy train or tighten our belts and have peace of mind within... My story is that you can stand up to a bully. Don't let the bully win, never let the bully win."

Betsy's story of withstanding the wrath of Lance is one in a long list. Cyclists Christophe Bassons and Greg LeMond have publicly spoken of Lance's bullying, as have doctor Prentice Steffen, Lance's former assistant Mike Anderson and O'Reilly. Aside from the statement she provided David Walsh, O'Reilly wrote a book condemning the endemic drug use in cycling and chronicling Lance's brutal behavior, called The Race to Truth.

Lance finally admitted to his doping days during a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey in January 2013. He said he first began using performance-enhancing drugs in the mid-1990s, claiming to have taken the hormones cortisone, testosterone and EPO, and conducted blood transfusions to boost his oxygen levels throughout his career. He insisted the last time he "crossed the line" with banned substances coursing through his system was in 2005's Tour de France.

In 1996, he founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer, which is now called Livestrong. The organization supports those affected by cancer, as well as their families, by supporting them financially, emotionally and physically. It has raised over $500 million to serve cancer survivors, advocate for cancer patients in policy debates and fight the stigma faced by many cancer survivors worldwide. In 2012, he stepped down from his position in the foundation, which continues to operate to this day.

Lance has three children with Kristin Richard, whom he was married to from 1998 to 2003, and two with Anna Hansen, whom he began dating in 2008. Between the two relationships, he was romantically involved with rocker Sheryl Crow, fashion designer Tory Burch and actresses Kate Hudson and Ashley Olsen.

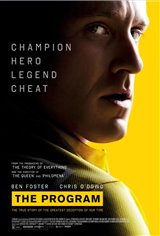

The Program, a film chronicling writer David Walsh's skepticism of Lance's unfathomable achievements, stars Ben Foster as Lance and Chris O'Dowd as David. Adapted from his book L.A. Confidential, the film is directed by Stephen Frears.

~Matthew Pariselli