Jesse Owens

The 1936 Berlin Olympics were expected to be a global statement for Aryan supremacy. Adolf Hitler publicly predicted the success of his Teutonic athletes and privately criticized America for its use of African American athletes. But it would be those very athletes who would secure America's success at the games. Out of 11 total gold medals awarded, six of them were to African American athletes. And out of those six golds, four of them were won by one athlete alone — 22-year-old Jesse Owens.

Jesse Owens was born James Cleveland Owens, known simply as "J.C.," on September 12, 1913 in Oakville, Alabama. He was the grandson of slaves, and the seventh child of a sharecropper father Henry and mother Emma.

He was a sickly baby, often ill with chronic bronchial congestion and pneumonia. By the age of seven, Jesse was brought into his father's sharecropping business; picking up to 100 pounds of cotton a day.

When he was nine, Owens moved with his family from Alabama to Cleveland, Ohio, going from a small-town, one-room schoolhouse to a full-fledged public school. Still known as "J.C.," the young man got a new name from a teacher who could not understand his thick southern accent and thought he said "Jesse" instead of "J.C." Jesse Owens as we know him today was born.

Owens began his athletic career in 1928, when his track potential caught the eye of Fairmont Junior High's coach Charles Riley. Riley took Owens under his wing, providing him with extra practice sessions and even treating him to dinners at his own home. Owens would credit Riley with refining his signature running style, telling him to run as if "the track were on fire" — with swift, fluid steps and an upright upper body. During this time, Owens would set the junior high school record by clearing six feet in the long jump and leaping over 22 feet in the broad jump.

This upward momentum continued well into high school, where Owens won the Ohio State Championship for three consecutive years. In his senior year, he participated in three track and field events at the National Interscholastic Championships in Chicago, setting records in the 100- and 200-yard dashes as well as the long jump.

The rising star was offered myriad scholarships to colleges all over the country but chose to attend Ohio State University, where former track and field star Larry Snyder was head coach of the Buckeyes track team. Snyder, born on August 9, 1896 in Canton, Ohio, was a pilot instructor during the first World War and boasted his own outstanding track career before he became a coach at OSU. Snyder would go on to coach Jesse throughout the rest of his career, including during his run at the 1936 Olympics.

Despite a lower back injury, and with the aid of Snyder, Jesse, now known as "Buckeye Bullet," chose to compete at the 1935 Big Ten Championships Ann Arbor, Michigan, where his career skyrocketed. In a span of approximately 45 minutes, he tied one world record in the 100-yard dash and broke three in the long jump, 220-yard dash and 220-yard low hurdles.

That same year, Jesse went on to compete in a total of 42 events, including four events at NCAA championships and three at the Olympic trials. He won them all. This consistent success gave Jesse the confidence to enter the 1936 Olympics. However, there was a caveat. That year the games would be held in Berlin, Germany, at the height of the Nazi regime.

Many believed Nazi Germany was using the 1936 Olympics as propaganda to publicly promote a united and peaceful Germany while masking the regime's antisemitic and racist policies. For the first time in Olympic history, many people, particularly in America, called for a boycott of the Olympic games because of Germany's clear abuse of human rights. President of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), Judge Jeremiah Mahoney, also a known Catholic, spearheaded this boycott. He believed participating in the games would endorse Hitler's Reich. Others in favor of the boycott included New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, New York governor Al Smith, Massachusetts governor James Curley and former member of the International Olympic Committee Ernest Lee Jahncke. Because of his beliefs, Jahncke was the first member in the IOC's 100-year history to be ejected from his position. A position which American Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage took over.

Brundage staunchly opposed the boycott and fought hard to send the U.S. team to the 1936 Olympics. He wrote in the AOC's pamphlet "Fair Play for American Athletes" that American athletes should avoid the "Jew-Nazi altercation." Determined, Brundage eventually swayed the AAU to vote in favor of sending America to Berlin. Forty-nine teams from around the world would compete in the 1936 games, more than any in Olympic history.

Many, including Owens himself, expected a hostile reception from the German people. But it was quite the opposite. While German officials denounced him, Owens arrived in Germany to throngs of fans who were enchanted by the young man. As he later recalled, he received some of the greatest ovations of his career in Berlin. He was even allowed to travel with and stay in the same hotels as the white athletes, a luxury not afforded to African Americans in many parts of America at that time. Owens would later, in 1984, have a street in Berlin named after him.

Owens was lauded for good reason — he took home an astounding four gold medals during his time in Berlin. His first three medals were for completing the 100 meter dash in 10.3 seconds (tying the world record), the long jump with a jump of 26' 5 1/4" (his first Olympic record) and the 200 meter dash in 20.7 seconds (his second Olympic record).

His fourth gold, however, caused a controversy, and not with the Germans — but rather, his fellow Americans. American Jews Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller were supposed to run for the U.S. on the 400 meter relay, however, they were replaced at the last minute by Owens and teammate Ralph Metcalfe. This decision was made by Coach Dean Cromwell and the American Olympic Committee, including President Avery Brundage, who were reportedly put under pressure by Hitler's officials. Cromwell claimed it was because they needed to assemble the fastest team possible.

Glickman was vocal in his belief that this decision was made because of antisemitism, as well as Cromwell and Brundage's desire to spare Hilter the embarrassment of seeing two Jews on the podium.

In his official report after the Olympics, Brundage refuted this claim and wrote, "An erroneous report was circulated that two athletes had been dropped from the American relay team because of their religion. This report was absurd."

Stoller, unlike his teammate, didn't believe antisemitism was involved, but did publicly state that it was "the most humiliating episode" of his life and promised to never run again during an Olympics.

Whether it was in fact racism, or something else altogether, Owens and his teammates went on to win gold for America, completing the relay in 39.8 seconds, beating the Olympic and world record in the process. Owen's extraordinary Olympic run came to a close and with it, he became the first American in Olympic Track and Field history to win four gold medals in a single Olympiad.

"It dawned on me with blinding brightness. I realized: I had jumped into another rare kind of stratosphere – one that only a handful of people in every generation are lucky enough to know," he later recalled.

Despite this massive achievement, the reality of being a person of color in 1930s America still followed Owens long after he returned home.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt failed to meet with Owens and congratulate him, despite this being the typical protocol with returning champions.

A report also arose that Hitler refused to shake hands with Owens. However, most historians and critics agree that Hitler opted not to shake hands with any of the athletes. Another report states that the leader of Hitler's Nazi Youth Movement, Balder von Schirach, suggested that Hitler meet Owens, to which Hitler replied, "The Americans ought to be ashamed of themselves for letting their medals be won by negroes. I myself would never shake hands with one of them." This report has not been verified.

Owens maintained that he was much more disturbed by the lack of recognition in his home country, by Roosevelt, who was a Democrat. After his return from Europe, Owens swiftly joined the Republican Party and campaigned for African American votes for candidate Alf Landon in the 1936 presidential election.

"Hitler didn't snub me — it was our president who snubbed me," he said at Republican rally in Baltimore. "[He] didn't even send me a telegram."

Many believed that this "snub" was a reflection of the systemic racism and racial hypocrisy still prevalent in American society, as evidenced by Owens' treatment upon his return. After a ticker tape parade was held for him in New York, Owens arrived at the Waldorf Astoria hotel for a reception held in his honor. Rather than take the guest elevator, reserved for whites only, he was forced to take the service elevator.

"After all the stories about Hitler, I couldn't ride in the front of the bus," he said. "I had to go to the back door. I couldn't live where I wanted. Now what's the difference?"

This was not the only problem that the talented athlete faced back in America. First, he was expelled from the American Amateur Athletics Union because he opted to stay in the U.S. and capitalize on his current fame, rather than compete with his fellow Olympians in Sweden. Prohibited from any more amateur sports appearances, his commercial offers all but vanished. He eventually resorted to running sprints against cars, motorbikes, dogs and horses. He even worked as a janitor and gas pump attendant.

This was an unusual trajectory for someone who, just months before, had reached the height of fame and achievement that Owens did. At that point, he had married his girlfriend Ruth and already had one daughter to support.

"People said it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do?" he asked. "I had four gold medals, but you can't eat four gold medals."

Owens later opened a dry-cleaning business in Cleveland but had to declare bankruptcy because his two partners turned out to be conmen, and was subsequently charged with tax evasion. This was a mere three years after his Olympic victory.

"After I came home...with my four medals, it became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite," he said. "But no one was going to offer me a job."

Eventually Owens settled into public speaking and public relations, a career which would finally offer him the comfortable living for which he had worked so hard.

He returned to the public eye in 1968 when he criticized the black power salute by African-American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the summer Olympics in Mexico City.

His statement against the salute showcased his continued disillusionment with the treatment of African Americans: "The black fist is a meaningless symbol. When you open it, you have nothing but fingers – weak, empty fingers. The only time the black fist has significance is when there's money inside. There's where the power lies."

Owens later amended this statement in his 1972 memoir I Have Changed: "I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the black man was concerned, that any black man who wasn't a militant in 1970 was either blind or a coward."

In his later years Owens made an effort to stay out of the public eye, particularly regarding political issues.

He wrote in his memoir, "For a while I was one of the most famous people on earth, but I soon discovered how empty fame can be and how easily it could be exploited by those who would use it, and me, for gain."

It took four decades for Owens to receive the recognition he so rightly deserved from the White House back in 1936.

In 1976, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald R. Ford, the highest possible honor bestowed upon a civilian and in 1979, he was presented with Living Legend Award by President Jimmy Carter.

He was also posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1990 by President George H.W. Bush.

Jesse Owens died at the age of 66 in Tuscon, Arizona on March 31, 1980 after a long battle with lung cancer. He is survived by his three daughters: Gloria, Marlene, and Beverly, as well as the Jesse Owens Foundation. The Foundation continues to carry on Jesse's legacy by providing financial assistance, support, and services to promising youths.

Coach Larry Snyder retired in 1960 and died two years after Owens, on September 25, 1982 at the age of 86.

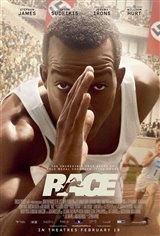

Canadian actor Stephan James stars as Jesse Owens, Jason Sudeikis plays his coach Larry Snyder, William Hurt plays AAU President Jeremiah Mahoney and Jeremy Irons plays AOC president Avery Brundage in the film adaptation of Jesse's early years, Race.

~Shelby Morton