Carnegie Hall has played host to several of music’s most influential and acclaimed artists.

The great American orchestras have been a staple at the venue since it opened its doors in the late 1800s. Jazz stars Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson and Miles Davis have also taken its stage. In the vibrant 1960s and '70s, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, the Beatles and Luciano Pavarotti stepped into the Hall’s spotlight as well.

Another name in Carnegie Hall’s history book is Florence Foster Jenkins. Her presence in the Hall’s past, however, resounds with a starkly different tone.

Born on May 19, 1868 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Narcissa Florence Foster was the child of Charles Dorrance Foster and Mary Jane Hoaglund. Charles was a well-respected lawyer, banker and member of the Pennsylvania legislature, while Mary was a homemaker.

Florence, who would drop the name Narcissa, discovered her budding passion for music as a child. She took piano lessons as a young girl and was drawn to the musical instrument that was her voice. Singing became the vocation she wanted to pursue, despite firm discouragement from her parents who forbade her from performing in public. Florence believed her voice to be pure and pristine and she refused to be told otherwise.

In a brave act of defiance – arguably the first in a life peppered with them – Florence fled her family’s nest around 1885, leaving her parents and their disapproving views behind. It’s reported at this time that she also met and married Philadelphian Francis Thornton Jenkins, a physician 16 years her senior.

When it became clear that Francis was unfaithful, their relationship dissolved and in 1902 they divorced. Without financial support, Florence decided she would carve out a living for herself as a piano teacher. She struggled to pay the bills.

Based in New York at this point, her life spun around in 1908 when she was introduced to well-connected New York City actor St. Clair Bayfield. The pair quickly bonded and he became her ardent advocate, number one fan and manager. Although they never married, they remained partners until she died, at which point he inherited her estate.

When Florence’s father passed away in 1909, she was afforded a sum of money, which she put towards voice lessons. She was devoted to her singing and longed to be publicly heard.

In 1912, Florence mustered the courage to perform the first in a series of annual recitals she would eventually stage. She sang in the foyer of New York City’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel, without the ability to carry a single tune, grasp a sense of rhythm or hit the upper registers. Florence fronted the bill for the balls, which would attract 800 guests per year, and she donated the proceeds to charities.

She inherited her family’s considerable fortune when her mother died in 1928. With the money she acquired, she expanded her number of performance venues to include concerts in Boston; Newport, Rhode Island; Saratoga Springs, New York and Washington, D.C.

Florence began developing her repertoire, specializing in the work of Mozart, Verdi and Brahms. Along with the pieces she would perform, her charisma and stage presence also fed into her reputation. One of her favorite encore songs to sing was Joaquín Valverde Sanjuán’s “Clavelitos,” a Spanish number about carnations. After she hit the last note, or made her attempt at hitting it, she would throw handfuls of rosebuds into the audience.

Her performance attire earned her recognition as well. Florence’s most famous costume was an elaborate ensemble of tulle and tinsel, which she accentuated with glamourous golden wings. Whenever she donned the outfit, she referred to herself as “The Angel of Inspiration.”

In 1938, Florence made the first of five 78 RPM recordings at the Melotone studio in New York City at her own expense. For her recordings, and for many other performances, she utilized the skills of accompanist Cosmé McMoon, a flamboyant man well-known in the city’s underground gay scene. The recordings produced became novelty items.

One recording she made in 1941 was of an aria from Mozart’s Magic Flute. A review in Time magazine said: “Last week a recording of this air, advertised entirely by rumour, enjoyed a lively little sale at Manhattan’s Melotone Recording Studio. It was recorded – to sell to her friends at $2.50 a copy – by Mrs. Florence Foster Jenkins, rich, elderly amateur soprano and musical clubwoman. Mrs. Jenkins’ nightqueenly swoops and hoots, her wild wallowings in descending trills, her repeated staccato notes like cuckoo in its cups, are innocently uproarious to hear.”

At this point, Florence had amassed a faithful following. Her uninhibited approach and endearing audacity are said to have attracted the likes of opera stars Enrico Caruso and Lily Pons. Journalist Brooks Peters would also later write that famous American musician Cole Porter never missed one of her shows and even composed a song for her.

All through Florence’s life, it was a dream of hers to perform in New York City’s esteemed Carnegie Hall. On October 25, 1944, she realized her goal.

In what was said to be the fastest sold-out concert in Carnegie Hall’s history, Florence sang her signature selections at the venue with the accompaniment of the Pascarella Chamber Music Society Quartet, flutist Oreste De Sevo and on piano, loyal Cosmé.

Florence's previous concerts were by invitation only, and her performances had never been reviewed in the mainstream press. Her concert at Carnegie Hall would be a first.

Florence filled the Hall, with all 3,000 seats occupied by the time her piercing voice took flight. Newsweek reported an additional 2,000 ticket seekers were turned away from Carnegie’s doors when it hit maximum capacity.

During the performance, Florence proudly asserted, “You will never again hear a voice like this in Carnegie Hall!”

In its review of Florence’s concert, Newsweek said, “Howls of laughter drowned Mme. Jenkins’s celestial efforts. Where stifled chuckles and occasional outbursts had once sufficed at the Ritz, unabashed roars were the order of the evening at Carnegie.” According to Bayfield, she was devastated by the terrible reviews.

Two days after her thrilling Carnegie Hall concert, Florence suffered a heart attack while in Schirmer’s Music Store. She collapsed and died a month later on November 26, 1944, at her luxurious Manhattan residence, the Hotel Seymour. She was 76 years old.

Trailblazing Florence followed her own desires. Author Stephen Pile gave her the distinction of “the world’s worst opera singer,” but also added, “No one, before or since, has succeeded in liberating themselves quite so completely from the shackles of musical notation.”

Throughout her life, she earned other titles too: “the diva of din,” “the first lady of the sliding scale” and “the queen of camp.”

The quirky singer was known for her eccentric behavior, as illustrated by Francis Robinson, former assistant manager of the Metropolitan Opera. Robinson would recount a 1943 incident where Florence reportedly gave a New York City cab driver a box of Havana cigars after the cab they were in crashed into another car - because she was convinced she could sing a high F note only following their collision.

Florence didn’t restrict herself to musical pursuits. She chaired the Euterpe Club’s yearly tableaux vivants, performed recitals to raise money for charity, founded and funded the Verdi Club for Ladies (which raised money for artists and musicians), served as president of the American League of Pen Women and also took the role of president for an estimated 12 other women’s clubs.

She didn’t live long enough after her Carnegie Hall performance to fully reap its rewards, but Florence’s storied life and effervescent spirit have since been paid tribute. At least two stage musicals have honored her textured tale, namely Glorious!: The True Story of Florence Foster Jenkins, the Worst Singer in the World by Peter Quilter and Stephen Temperley’s Souvenir: A Fantasia on the Life of Florence Foster Jenkins.

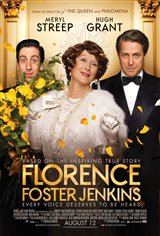

Her life and Carnegie Hall concert are also the subject of the upcoming film Florence Foster Jenkins, directed by Stephen Frears. The picture stars three-time Oscar winner Meryl Streep as the tone-deaf singer and Hugh Grant as the supportive St. Clair. ~Matthew Pariselli